If you’ve ever had a discussion where someone says “net profit” and someone else says “net income“, you’ve probably asked yourself: Are they talking about the same thing?

In many companies, these terms are used interchangeably. And in most cases, that’s fine. But in complex organizations, especially those with multiple business units, international operations, or frequent board reporting, this seemingly small difference can lead to serious reporting misalignment.

Read more: A Complete Guide to Financial Statement Analysis for Strategy Makers

If we set aside terminology, this is more about ensuring everyone uses the same definition of the bottom line. If they aren’t, forecast-to-actual comparisons become unreliable, monthly reports require more reconciliation, and your team wastes time explaining numbers instead of analyzing them.

This article breaks down the difference between net income and net profit, shows where confusion can creep in, and outlines practical steps you can take to fix it without adding more reporting overhead.

Net Income vs Net Profit: Are They Really the Same Thing?

In theory, net income and net profit refer to the same financial result: what’s left after you subtract all costs, OPEX, interest, and taxes, from total revenue. But in practice, teams across your company might be using those terms differently, especially when building budgets, forecasts, or group-level reports.

This isn’t just semantics. It creates friction in:

- Budgeting and planning cycles

- Cross-subsidiary consolidation

- Monthly and quarterly reporting alignment

These kinds of issues show up all the time in complex organizations, especially those running multiple forecasts per year or managing planning across subsidiaries:

- In some manufacturing groups, local controllers define “net profit” as EBITDA minus CAPEX, while group finance uses net income per IFRS. When comparing actual vs. plan, the variance analysis becomes unreliable, not because of errors, but because teams are using different profit formulas.

- In pharma companies, BU managers are often incentivized on “net profit”, but the bonus scheme doesn’t clarify whether that’s before or after tax. The result? Regional controllers forecast toward different targets, distorting group-level margin expectations.

The key issue: everyone thinks they’re talking about the bottom line, but they’re using different formulas.

Where This Confusion Shows Up in Real Businesses

Confusion around “net income” and “net profit” becomes a problem when these terms are used interchangeably but applied differently across teams. That’s not a terminology issue but an operational one.

Here are the most common points where this creates friction inside mid-sized and large enterprises:

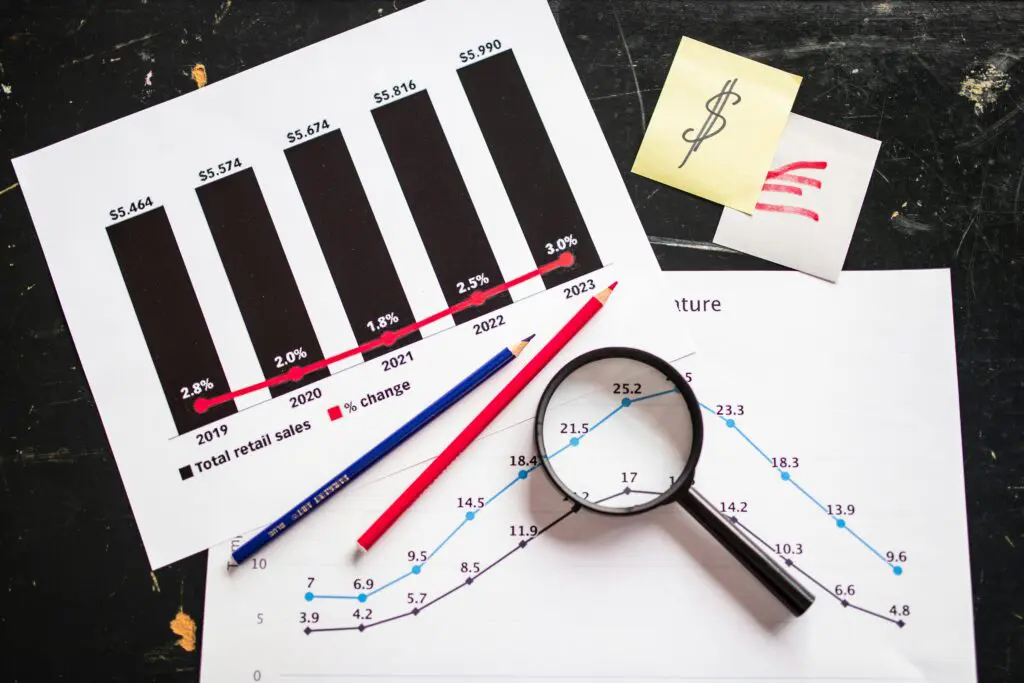

1. Forecasts don’t align with actuals

You set financial targets centrally, but each BU sends in forecasts based on their own version of “net profit.” Some include deferred taxes, others don’t. One team reports after minority interest, another before it. The final comparison against actuals becomes unreliable.

KPMG found that a major blocker to forecast reliability is the lack of standardization in data definitions and processes, leading to misalignment between strategic goals and operational plans.

Result: Finance wastes time explaining variances that aren’t based on performance, but on inconsistent logic.

2. Performance discussions turn into accounting debates

In monthly reviews, business leaders argue over margins instead of actions. Why? Because “net profit” means different things to different teams:

- Sales includes commissions and bonuses.

- Controlling strips out non-operating items.

- Group finance expects IFRS-aligned net income.

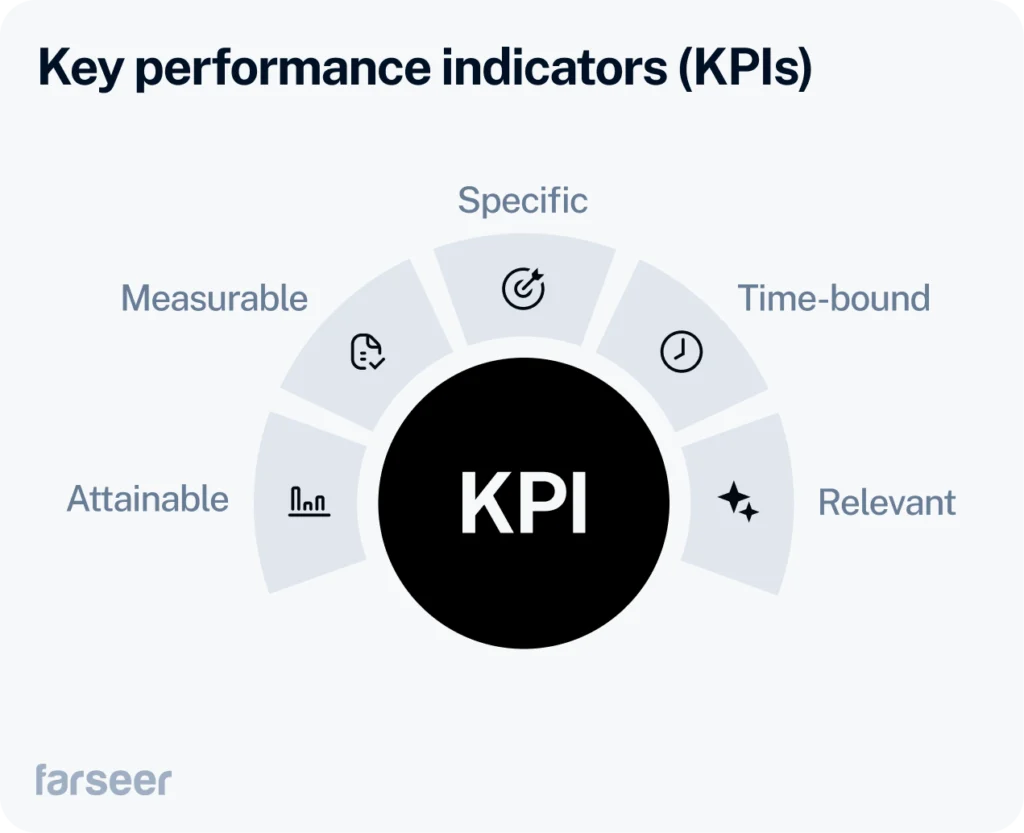

According to Gartner, only 9% of finance teams say their planning is fully aligned across strategy, operations, and reporting, due in part to KPI inconsistency.

Result: Meetings stall, and finance becomes a referee instead of a strategic partner.

3. Group reporting slows down due to manual standardization

Let’s say one business unit submits net profit excluding intercompany allocations, while another includes them, because their local reporting models differ slightly. The margin deviation is small, but the inconsistency triggers questions from group finance and auditors.

Gartner highlights this issue directly: fragmented metric definitions and disconnected planning tools are a top reason why group close cycles drag out and audit preparation becomes reactive.

Result: Closing takes longer, confidence in the numbers weakens, and audit friction increases.

These are not edge cases. They’re everyday examples of what happens when finance doesn’t standardize key KPIs. And they get worse the more business units, planners, and reports you manage.

Tools like Farseer help solve this by embedding net profit logic directly into planning models, so every forecast, budget, and group report speaks the same language, without manual corrections downstream.

How to Fix This Confusion (Without Creating More Process Overhead)

The fix isn’t another policy document or glossary buried in a shared drive. If you want alignment on “net income” vs “net profit,” it has to be baked into the way planning happens, at the point of entry, not just in the final report.

Here’s what high-functioning finance teams do to reduce interpretation risk and standardize bottom-line reporting:

1. Define KPIs once, and embed them in the system

Whether you use net income, net profit, or another margin metric, define it clearly in one place, then apply it across your entire planning workflow. That includes forecasts, budgeting templates, and performance dashboards.

Farseer users, for example, standardize key KPIs inside reusable planning models. Instead of leaving it up to each BU controller to define net profit, they use formulas locked into the system, ensuring the same logic runs everywhere, from top-down targets to bottom-up submissions.

2. Align on KPI definitions before the budgeting season starts

Make KPI review a formal part of your annual planning process. Before anyone builds their forecast, get agreement on how you define profit, margin, and EBITDA, and make those assumptions visible in every template.

If you’re running planning in Excel, this might mean building a cover sheet with exact KPI logic. If you’re using Farseer or another FP&A platform, include the definition directly in the input forms.

Read more: FP&A Software for Modern Finance Teams: Compare the Best Tools in 2026

3. Stop relying on manual corrections after the fact

It’s common for group finance to “fix” reports at the end of the process, adjusting for different BU logic during consolidation. But this creates a false sense of control. By the time you’re correcting numbers, the underlying decisions have already been made.

Instead, move the standardization upstream. Use shared templates, controlled calculations, and automated checks that catch mismatches before they roll up.

Read: Financial Reporting Automation – What It Actually Fixes (And Doesn’t)

4. Audit your planning inputs, just like you audit the outputs

Every quarter or cycle, do a spot check: are planners using the same definitions they agreed to? Are KPIs applied consistently across regions and BUs? You don’t need a complex framework, just a regular review to prevent drift.

With a structured FP&A system like Farseer, it’s easier to monitor this because you can audit formula logic across all templates from a central admin view.

These fixes don’t require more headcount, more meetings, or heavy documentation. What they require is a shift from interpretation to structure, so that everyone from junior controllers to senior management sees the same “net profit,” no matter where they sit.

Why Small Fixes Like This Matter More as You Grow

It’s easy to dismiss the difference between “net income” and “net profit” as semantics until it costs you days of reconciliation, weakens your forecast accuracy, or undermines a board presentation.

Small misalignments don’t stay small in growing organizations. As complexity increases they scale into larger reporting risks.

And when planning is still run through spreadsheets or disconnected systems, these risks surface more often and are caught too late. The result? Slower closes, more explanations, and less time for actual analysis.

Finance teams that address this early, by standardizing key KPI definitions and embedding them into the planning process, save time, increase reporting confidence, and avoid strategy decisions based on mismatched numbers.

Farseer was built for exactly this kind of structured, aligned financial planning. Whether you’re managing planning across two plants or twenty countries, clarity starts with shared definitions and ends with numbers you can actually trust.

Want to see how Farseer handles this in practice?

Đurđica Polimac is a former marketer turned product manager, passionate about building impactful SaaS products and fostering connections through compelling content.