Financial statement limitations can impact your decision-making. Picture this: you’re preparing for a very important quarterly meeting with your executive team. The statements are ready – carefully compiled and proofed. Halfway through the meeting, you’re done with the presentation, everything is running smoothly – based on financial statements it seems that your revenue is growing and the company has solid profitability.

Read: A Complete Guide to Financial Statement Analysis for Strategy Makers

But all of a sudden you’re swamped with questions like “How are we tracking against our strategic goals?” “What’s driving the sudden dip in one product line?” “What’s the outlook for the next quarter if material costs rise?” And you realize the numbers in front of you only paint half the picture.

This is the reality for many businesses.

Though there isn’t a good financial report without them, certain financial statement limitations need to be considered before being able to present your results with confidence. Let’s go through the most common ones and tips on how to overcome them.

Key Limitations of Financial Statements

Limitation #1: Historical nature of data

Limitation number one – financial statements primarily focus on past performance. They are here to offer an overview of what has already happened within a specific period.

Which is not completely bad – this is crucial for understanding trends. But they fall short in predicting future outcomes or addressing potential risks. For instance, if you’re working in a dynamic industry or industry with seasonal changes, relying only on last quarter’s revenue figures to forecast demand can lead to inaccurate projections and/or missed opportunities.

How to overcome this?

To overcome this financial statement limitation, businesses can include advanced FP&A tools alongside traditional financial statements. These tools integrate real-time data and predictive analytics, which lowers the chance of mistakes.

For example, companies like Walmart use advanced analytics to monitor trends in consumer behavior, such as spikes in demand for essential goods. This allows them to adjust inventory and supply chains proactively, and minimize losses. When you incorporate forward-looking models and scenario planning, your company can anticipate future trends better, adapt to market shifts, and align strategic goals with potential outcomes.

Limitation #2: Missing non-financial factors

Let’s face it – financial statements are great for showing measurable outcomes like profits or expenses, but they leave out the “human” side of the business. Think about factors like how satisfied your customers are, how engaged your employees feel, or how strong your brand’s reputation is. These intangibles are often the true drivers of long-term growth. And still, they don’t show up in the numbers on a balance sheet.

Take a retail chain, for example. It might cut costs by reducing staff or skipping employee training programs. On paper, it looks like a win – expenses go down, and profit margins go up. However, over time, this approach can disrupt the customer experience, which leads to lower brand loyalty and declining sales. The financial statements won’t immediately reflect these risks, but this doesn’t mean that the damage isn’t done.

How to overcome this?

To close this gap, businesses can use tools that track both financial and non-financial performance. For instance, a balanced scorecard might combine metrics like revenue with customer satisfaction scores or employee retention rates. A manufacturing company could use dashboards to track machine downtime alongside worker productivity and safety incidents. This approach gives decision-makers a more holistic picture of what’s driving their success – or holding them back.

Limitation #3: Standardization vs. customization

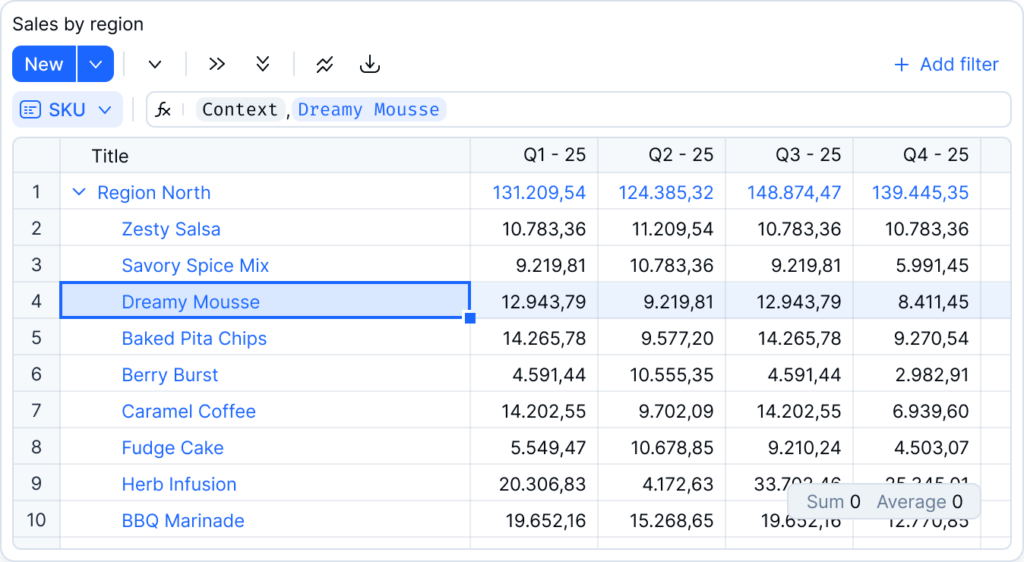

Financial statements are built to follow strict rules like IFRS or GAAP to ensure everyone – meaning investors, regulators, and stakeholders – can easily compare and rely on the data. This consistency is great. But it often doesn’t meet the specific needs of internal teams. Imagine a multinational company trying to understand why profits differ across regions. The aggregated financial statements might show overall profitability, but they won’t break down the performance by country or product line where you can find actual insights.

Here’s an example: a global consumer goods company wants to pinpoint why a particular product isn’t selling well in a specific region. Standardized statements might only show that overall sales are steady, which doesn’t tell you much about regional struggles. But by generating a custom report focused on SKU-level performance in that region, the company could discover a pricing issue or a supply chain delay that ultimately impacts sales.

How to overcome this?

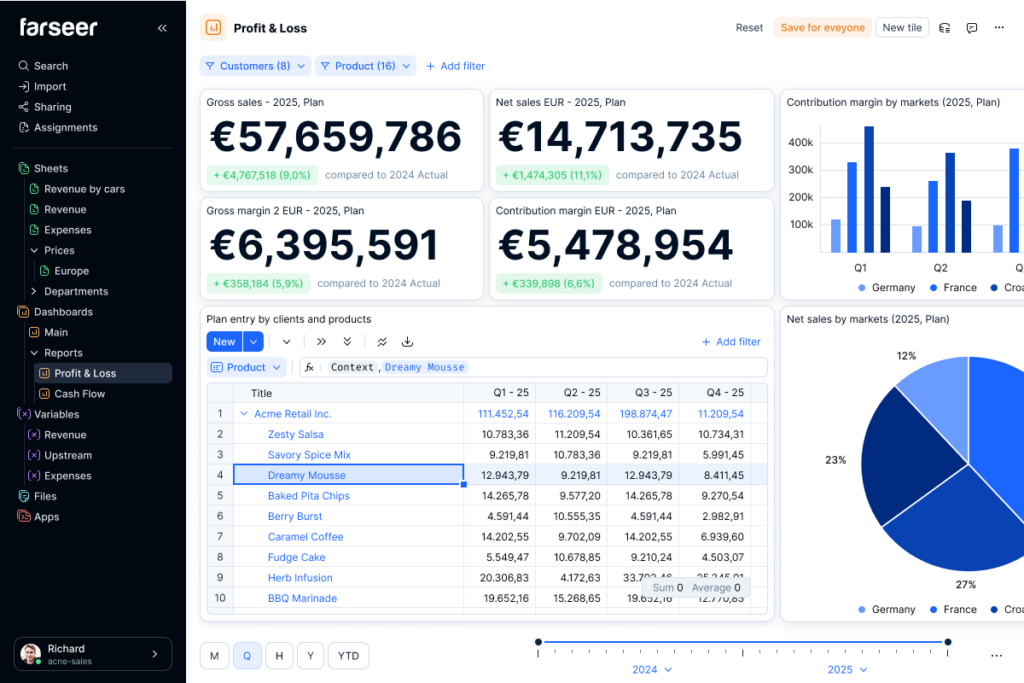

To solve this, many companies turn to advanced FP&A tools that allow for customized reporting. These systems let finance teams drill down into specific data sets, whether it’s regional profitability, department-level costs, or individual product performance. For instance, a manufacturing company could use these tools to pinpoint which factory has the highest costs and focus on improving its efficiency.

Limitation #4: Personal choices in accounting

Accounting isn’t always as black and white as it seems. There’s a lot of subjectivity involved, especially when it comes to decisions like how to depreciate assets or how to value inventory. These choices can really change the way a company’s financial statements look.

For example, let’s say two companies buy the same equipment, but one uses straight-line depreciation (which spreads the cost evenly over time) while the other opts for an accelerated depreciation method (which records more of the cost upfront). Even though the equipment is performing the same, the company using straight-line depreciation will show higher profits in the short term because their expenses are lower.

How to overcome this?

To make these differences clearer, it’s important for companies to stick to consistent accounting practices that match their business and industry needs. Transparency is key – by including detailed notes in the financial statements, businesses can explain why they’ve made certain choices and what impact those choices have. Companies can also use scenario modeling in financial planning tools to show how different accounting treatments might affect their bottom line, helping everyone get a clearer picture of the company’s financial health.

How to Overcome Financial Statement Limitations with Modern Tools

Modern financial planning and analysis (FP&A) tools are game changers when it comes to addressing financial statement limitations. While financial reports give us an image of the past, these tools offer a much richer, forward-looking view that helps businesses make smarter decisions.

As mentioned, in fast-moving industries like FMCG (fast-moving consumer goods), scenario planning can be incredibly useful. It allows companies to model the financial impact of things like supply chain disruptions or sudden changes in consumer demand. This way, businesses can be prepared and have strategies ready before issues arise.

Real-time forecasting is another powerful feature. By pulling in operational data, these tools give decision-makers the ability to adjust quickly as market conditions change, ensuring they stay ahead of the curve.

And then there are dashboards and data visualization tools, which turn raw data into clear, interactive visuals. These give a better understanding of key performance indicators (KPIs), making it easier for leaders to spot trends and take action—whether they’re looking at the big picture or zooming in on specific details.

Incorporating these modern tools helps companies transform their financial data into a strategic resource that drives growth and helps them achieve long-term success.

Conclusion

While financial statements are essential, they often fall short of providing the insights needed for agile, forward-looking decisions. They show where you’ve been but not where you’re going. Addressing these limitations requires more than just analyzing the numbers – it calls for modern tools and approaches that bridge the gap between static reporting and dynamic decision-making.